3 (More) Benefits of Export Manufacturing in Mexico and Why It Matters

Much has been written about the almost universal benefits of manufacturing. You can check out Dani Rodrik’s essay about industrial development and stylized facts here for example. Among the most prominent messages are that historically, industrialization and manufacturing exports are the most sustainable and significant drivers of high growth rates for virtually all countries and regions over time. This is both a historical fact on the industrialization experience of European pioneers and later-on emulators. This fact of life holds across time for individual samples of countries and comparatively among regions as well (economies with greater manufacturing exports and efficiency are those which have mostly achieved growth, and somewhat arguably, robust development levels).

Export manufacturing is also particular because it causes unconditional convergence, which is a term to convey that workers’ productivity in emerging countries tends to converge towards the productivity levels of richer economies with the same manufacturing export sector installed. Say, workers in the 1990’s facilities which manufacture air conditioning appliances in Mexico tend to produce the same output per worker (over time) as air conditioning machine producers such as Canada, Japan, etc. Of course, this stylized fact has some caveats, and is not necessarily unequivocal, but overall, on average, manufacturing industries in developing economies tend to converge towards the labor productivity levels of those same industries in richer countries. Which means that workers get better at what they do in tandem with firms’ efficiency and operations; somehow a driver of better wages and profits, and more human capabilities and know-how (with arguable positive spillovers in education and health in a community). In this regard, manufacturing differs from modern services in productivity benefits because of this very special and positive unconditional component. Also, in contrast, manufacturing has traditionally worked as a rural workforce absorber in urban settings through industrialization. Undoubtedly there are limiting considerations today regarding the unconditional welfare gains of exports manufacturing that were not that prevalent decades ago. Such as:

i. Environmental and sustainability considerations (although in some instances, the ecological impacts have been shown to be decreasing);

ii. New automation realities which somehow frustrate manufacturing relocation and their expected benefits, not least because of skilled labor shortages. Some automation technologies, while they could increase labor productivity, may in fact not increase wages for workers despite the productivity increase and decrease the added value share of labor in exported products. Acemoğlu, most notably has written extensively about this topic.

iii. National security concerns at play (particularly for strategic industries such as advanced electronics, pharmaceutical and medical devices or processed rare elements). DoD’s address on critical minerals as vital to national security, or complexities surrounding semiconductors foundries and geographical reliance.

iv. Competition from low-wage countries (sometimes backed by poor labor conditions) undermining the competitiveness of manufacturing in higher-cost countries (Mex.), while sluggish economic growth and high interest rates might make financing projects increasingly challenging and demanding higher profitability rates.

While these are nonetheless significant in discerning the convenience and viability within the economic policy toolkit of North America and Mexico, 3 crucial descriptions on the benefits of Mexican manufacturing are salient and evermore important. These should be present for any policymaker going forward and particularly amidst the dynamic reiterative tariffs’ scenario.

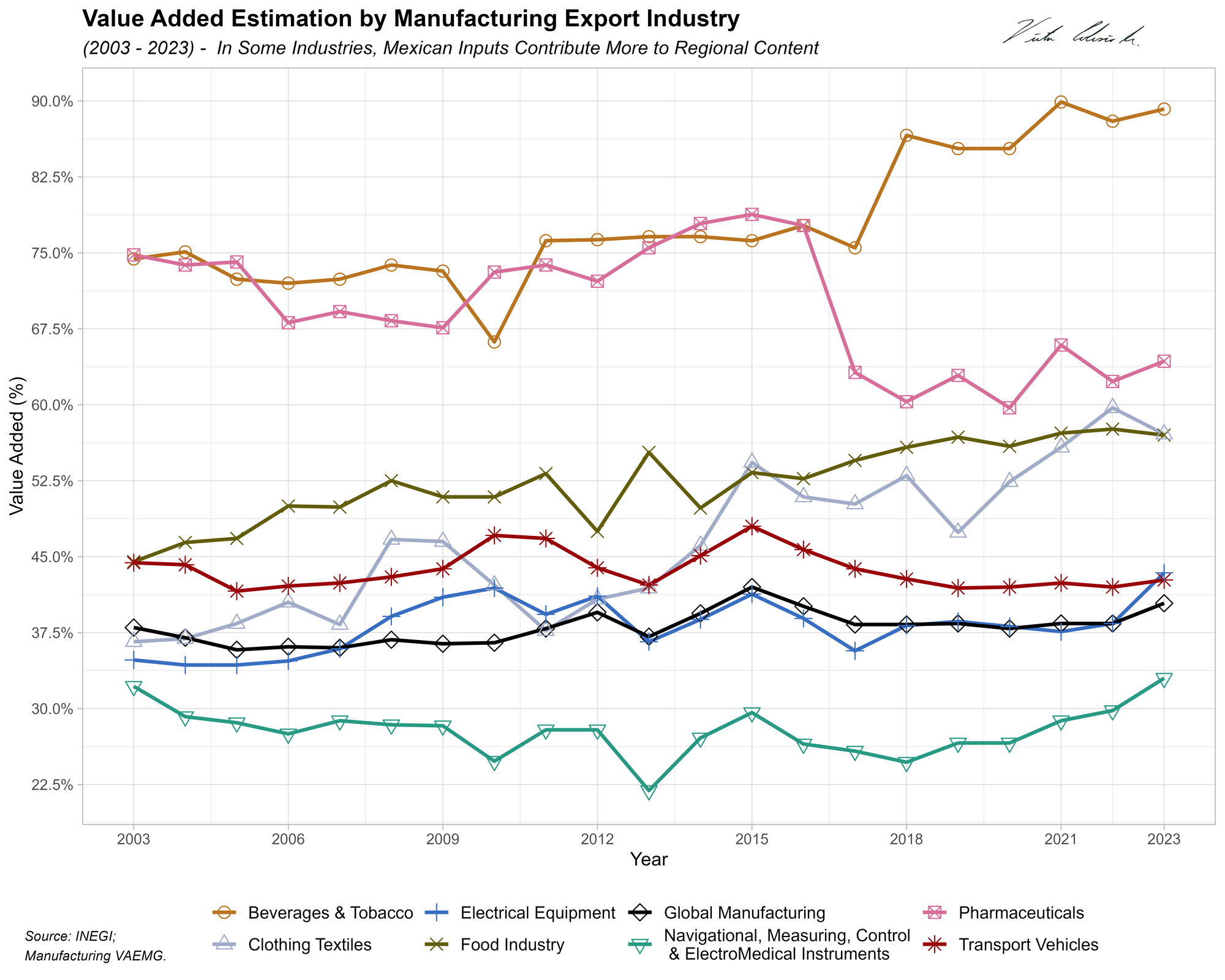

i. Value-added; some sectors display better payments to production factors than others (which are partially in turn, better wages for workers and overall payments to production factors).

i.a. A corollary of the previous is that these better-than-other sectors should be highlighted as those with more positive externalities and spillover effects transforming education institutions and environments in the Mexican landscape. It should be discerned that not all manufacturing, despite the FDI announcements or plans to promote a domestic industry, is positive in human development terms (rudimentary clothing textiles which is intensive in hydric resources, something that Mexico lacks in its manufacturing region vs. consumable medical supplies or equipment, requiring more sophisticated technicians).

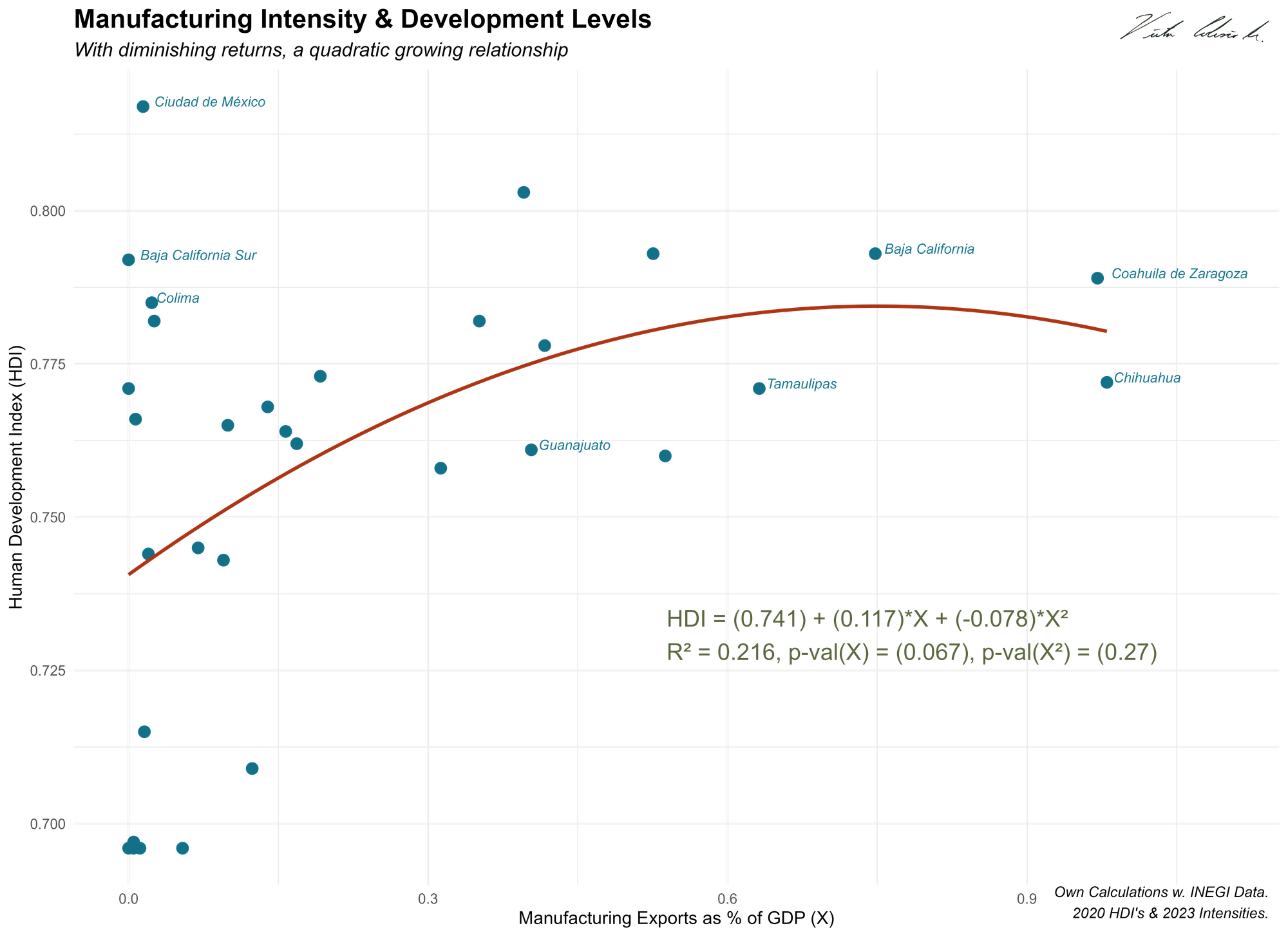

ii. States which are more export manufacturing intensive display better human development indicators (health, education, and quality of life metrics). This is reasonable to expect given that advanced manufacturing sectors create spillover effects that boost incomes, support public investments, and enhance overall socioeconomic well‐being.

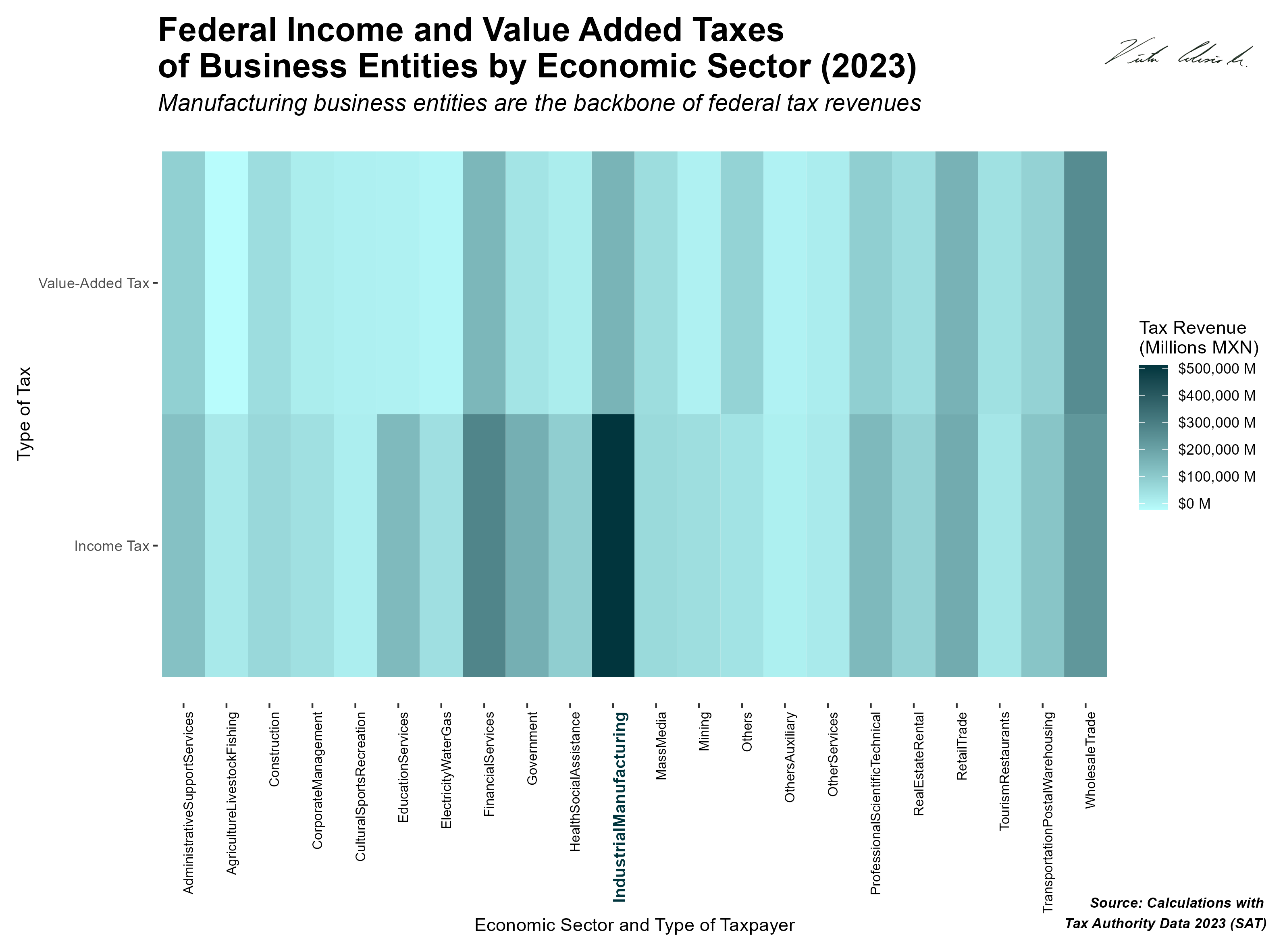

iii. Noticeably missing from the public conversation, export industrial manufacturing makes up most of the fiscal contributions in Mexico both in added value and income taxes. They are the bulk and backbone of Mexico’s capacity to have social programs and institutions.

To support the previous 3 arguments, here are 5 descriptive images partially summarizing the findings.

Average value-added content for Mexican export manufacturing oscillates between $35 to $42 out of every $100 exported when considering all the manufacturing sectors; with a 10-year historical average of $38. Some sectors perform better than others; beverages is a notorious national industry success, ubiquitous in the different brands and shelves across the U.S. (almost 90% of what is exported in beverages to the U.S. is Mexican content). While other industries such as those in precision & electromedical instruments reflect a more complex supply chain integration; supported greatly by intermediate inputs of diverse country origins. While value-added is not necessarily a measure of the quality of the jobs related nor of the export-size, it is however a direct proxy of labor content paid (wage mass) as well as firms’ utilities and payments to capital in Mexico. More of this should be indicative of where some industries are more self-sufficient in their input and production process. These kinds of indicators, adapted to local contexts, should be the guidance of subregional governments in their promotion activities, diversification efforts and strengths assessment grounded in realistic standing. This measure is probably also relatable to competitiveness terms (allowing for global benchmarking).

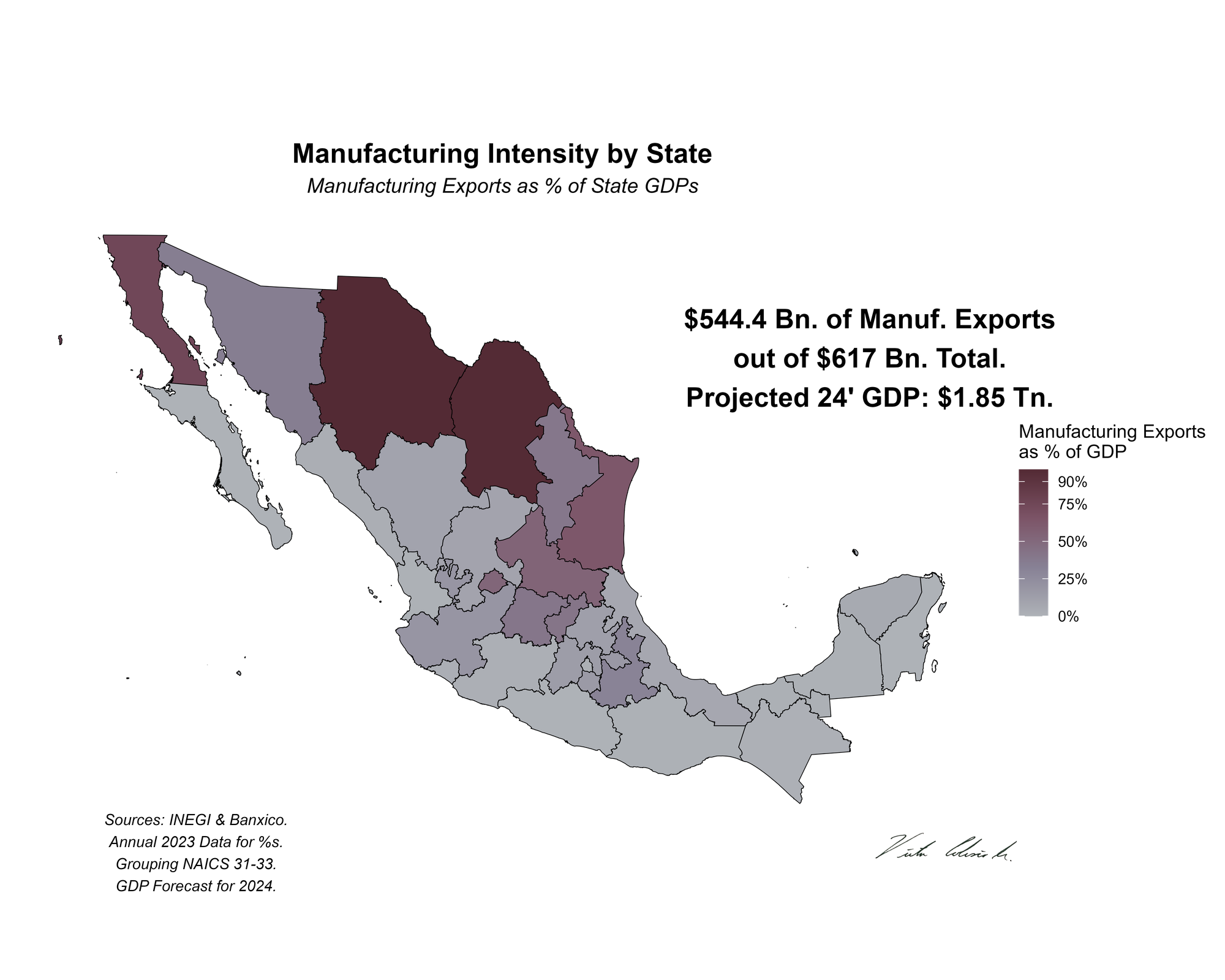

Nothing new under the sun. Goods manufacturing exports exceeded $544 Bn. USD in 2024; out of a $617 Bn. universe of exported merchandises (which is greater than Ireland, Israel, Singapore or Sweden’s entire GDPs of 2023). We tend to think of Mexico as an extractive industries country, or at least where most of its competitive edge is (minerals and avocados as discourse examples). And quite the contrary, manufacturing exports comprise 88% of total exports (extractives for example accounts for $10.8 Bn., while agricultural and livestock make up $23.3 Bn. out of our export basket, that is to say 3.7%). More surprisingly, while automakers are the traditional backbone of Mexican manufacturing and exports, auto exports only make up a third (31%) of total exported goods. That leaves a vast universe of non-auto exports which account for $360.5 Bn. USD in goods paid in a year in salaries to Mexican workers and returns on capital and investment for firms. Giving an understanding of the complexity of the North American integration with regards to more vital manufactured goods rather than just automobiles or air-conditioners. Furthermore, the previous map of the country reveals what is widely known as Many Mexicos, further emphasizing that the most manufacturing intensive states are along the northern border. Making the case for a more export oriented market as well as a more North American friendlier mindset. 83% of manufacturing exports are concentrated in just 10 states (out of which 6 are along the northern border and concentrate 2/3rds of total manufacturing exports); which are the highlighted on the previous map.

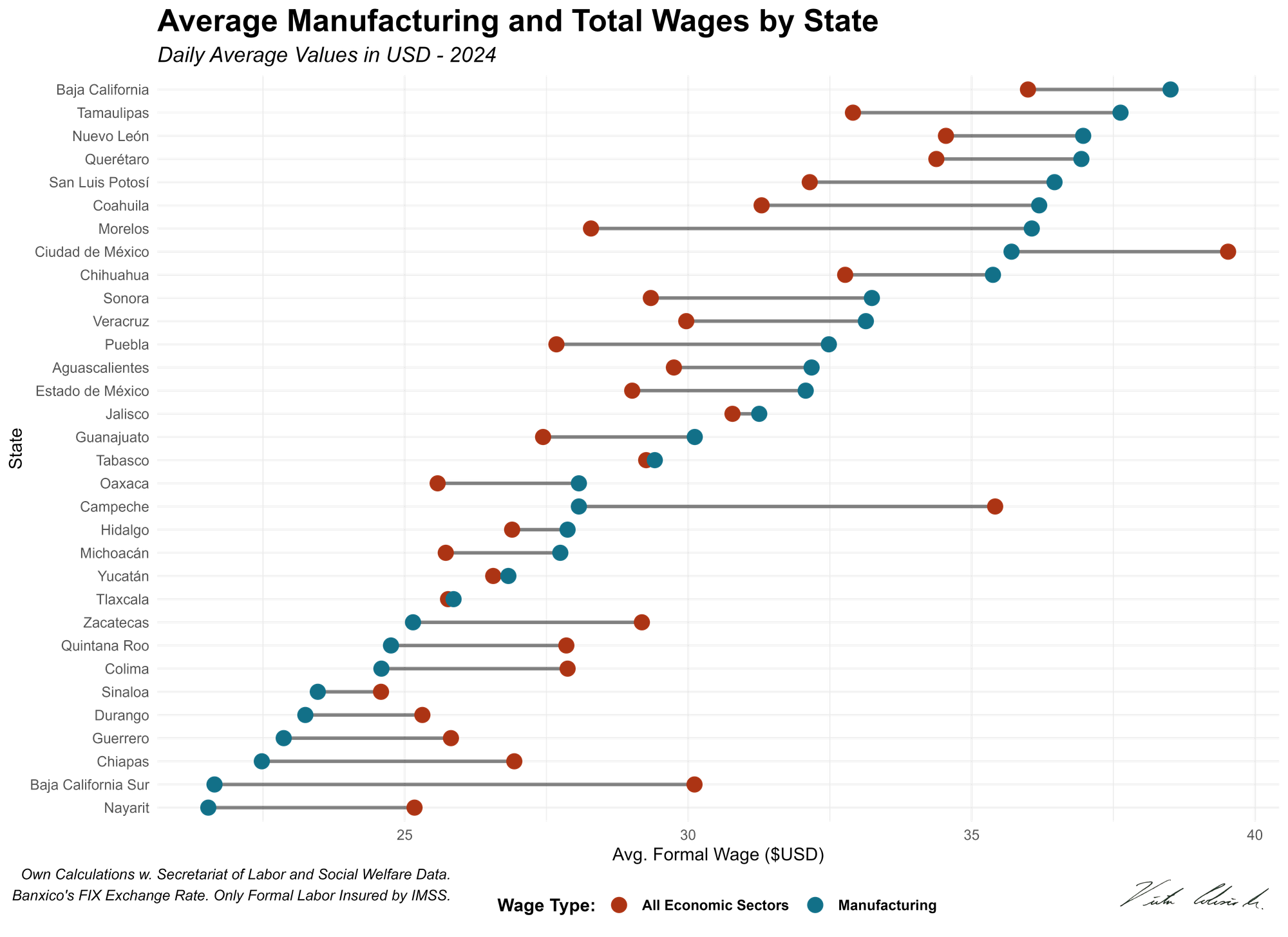

Furthermore, these states (Chihuahua, Baja California, Sonora, Coahuila, Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosi), when arranged in descending order according to their manufacturing wages, display the highest daily rates. Except for a couple of states that have outstanding services sectors in the previous dumbbell graph, manufacturing wages are higher than the overall economic daily wages (blue dots vs. red dots). And the more manufacturing intensive the state is, the better the daily wage rate. This is probably even more salient if a closer look into manufacturing sub-sectors is conducted.

Moreover, when mapping Human Development Indexes (the vertical axis of the previous scatterplot), which summarize life expectancy, expected years of schooling, and income per capita (a proxy for a decent standard of living); again, the more manufacturing intensive the state is, the better its development metrics and the higher its generalized wages. The previous scatterplot should serve as a basis for a dynamic analysis to show once and for all that compelling development mostly occurs in the more export-oriented and manufacturing intensive regions of the country.

When it comes to government sources of revenue, industrial manufacturing is the most significant basis of federal tax revenue. Making up at least 17.2% ($667.8 Bn. MXN) of total value added and income taxes collected ($3.8 Tn. MXN), which is more than $1 out of every $6 pesos (MXN) of taxes collected.

By contrast, individual taxpayers make up 3.1% of tax income revenue, while industrial manufacturing' taxes make up for more than 2 percentage points of total GDP. They also contribute 9.4% of the amplified public sector’s total revenue (~$7 Tn. MXN) which includes all oil, taxes, royalties and public incomes collected.

That’s almost $1 out of every $10 pesos that are direct government (primary) revenue, excluding income derived from debt instruments. Consider all the government expenditures made possible by industrial manufacturing. The taxes generated from this sector amount to 2/3rds of what the country paid in financial costs to service its total public debt ($1 Tn. MXN in 2023) and exceed the federal public sector’s total spending on materials and supplies by 65% ($403.3 billion MXN in 2023).

Wrapping Up: Bilateral Economic Policy, Positive Impacts of Industries on Communities, and Fiscal Contributions

Diverse conditions across states call for a tailored policy approach both domestically and in international relations. Regions with advanced industrial capacities may benefit from targeted measures that consolidate their competitive advantages in tandem with U.S. national strategic objectives. While areas in earlier stages of development require distinct support strategies, say, for supporting domestic labor force and exploring diversification opportunities. This nuanced framework should also be reflected in international trade policies; for instance, U.S.-Mexico trade relations could benefit by considering the internal regional variations of Mexico rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all stance. Recognizing the interplay between regional competitiveness and national security can lead to more balanced and mutually beneficial outcomes.

Some sectors tend to generate more positive human development outcomes than others. They are typically associated with higher productivity, better employment opportunities, improved wages, and stronger development metrics. Moreover, these industries often have beneficial spillover effects, supporting the emergence of higher education institutions and complementary services such as healthcare or technical centers (consider, Tec de Monterrey or solid public technological institutes in the Northwest). Growing up in a community centered around advanced manufacturing—like a medical devices’ facility partnered with a technological institution—can lead to a markedly different perspective compared to communities focused on mining, extractives or traditional textiles.

Fiscal contributions, are often considered secondary to GDP impacts in general estimations against tariffs. However, export manufacturing firms, despite their substantial contributions, are not sufficiently recognized for their role in both labor and fiscal support. Both essential in sustaining the Mexican Welfare State (however increasingly compromised). The states which host these industries deserve greater acknowledgment, but also must be held to a higher standard of accountability in their government exercise, for their pivotal support in reinforcing national fiscal stability.

Furthermore, the industrial composition of a region influences local culture, Worldview (in the fullest sense) and recreational opportunities. These differences are also reflected in the type and quality of local leisure infrastructure, ranging from well-developed parks and cultural centers to areas with a predominant focus on resource extraction and low-wage labor. Some sectors promote greater environmental sustainability and require higher levels of technological sophistication, skilled labor, but also nurture a workforce imbued with a globally integrated ethos—workers who are complemented by international values / beliefs and probably have a more basic appreciation of globalization or international trade. While other sectors or regions may depend more on resource-intensive practices and adopt a more defensive stance. They might favor local self-reliance and more traditional or nationalistic economic paradigms.